A Life of Science

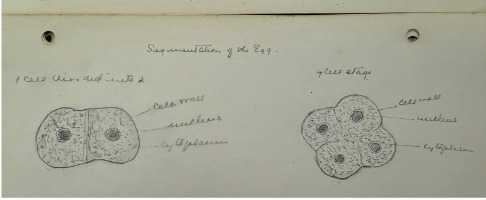

At MIT Katharine had set her sights on one day becoming a surgeon after graduation. Her course notes show her interest in physiology, with detailed illustrations of human and animal anatomy accompanied by copious notes.

However, in 1904, three months after she graduated from MIT, she married Stanley McCormick - a childhood acquaintance and the heir to one of the wealthiest American industrialist families of the time, and her plans were set aside. Within a year of their marriage Stanley began exhibiting signs of serious mental illness. His condition was described as “dementia praecox,” what we know today as schizophrenia.

Katharine was determined to find the best treatment for her husband. Over the years, she hired doctors and psychologists to undertake his care, but his condition did not improve. By the late 1920s, a public legal battle broke out over his care. Katharine challenged his doctors to look beyond Freudian psychoanalysis, and investigate biological causes for schizophrenia.

Dr. Edward Kempf, a leading American psychiatrist enlisted to treat Stanley, flatly rejected her position and refused to undertake any endocrine treatment in addition to psychotherapy. Ultimately, Katharine prevailed and Stanley was removed from Kempf’s care. Her instincts about a link between schizophrenia and the endocrine system had been ignored, but she was vindicated by research conducted decades later and still ongoing today.

Her drive to find a cure for Stanley also led her to fund and establish the Neuroendocrine Research Foundation at Harvard Medical School (1927-1947), and to subsidize the scientific journal Endocrinology.